Cultivation, Rumination, and Fermentation

Answering the question of the cursed earth

Cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of the life; thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field; in the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return.

Genesis 3:17-19

The curse given to Adam upon his exile from the garden is a fundamental problem in the Bible. Not only is man given over to death, but the earth has been cursed as well. Therefore, the question of the redemption of man is wrapped up in the question of the redemption of the earth. The story immediately following the expulsion from the garden, that of Cain and Abel, describes two ways of answering the problem of the “cursed earth:” cultivation and rumination. What are cultivation and rumination and why do they fail at answering the question of the cursed earth? How is the problem of the cursed earth ultimately resolved? My aim is to illuminate the patterns of cultivation and rumination as answers to the question of the cursed ground, and to show that fermentation becomes a synthesis that properly answers the question.

The story begins with the birth of two brothers: Abel was a “keeper of sheep”, while Cain was a “tiller of the ground.” Keeping sheep and tilling the ground are both ways of producing food. Rene Guenon offers a helpful insight, linking each of the brothers with a primordial way of being:

Cain is represented in Biblical symbolism as being primarily a farmer and Abel as a stockmaster, thus they are the types of the two sorts of peoples who have existed since the origins of the present humanity, or at least since the earliest differentiation took place, namely that between the sedentary peoples, devoted to the cultivation of the soil, and the nomads, devoted to the raising of flocks and herds

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, p. 145

To draw out the implications of each of these ways of being, we will need to explore the patterns of farming and shepherding as they relate to the earth and the cycles of time. I will begin with Cain.

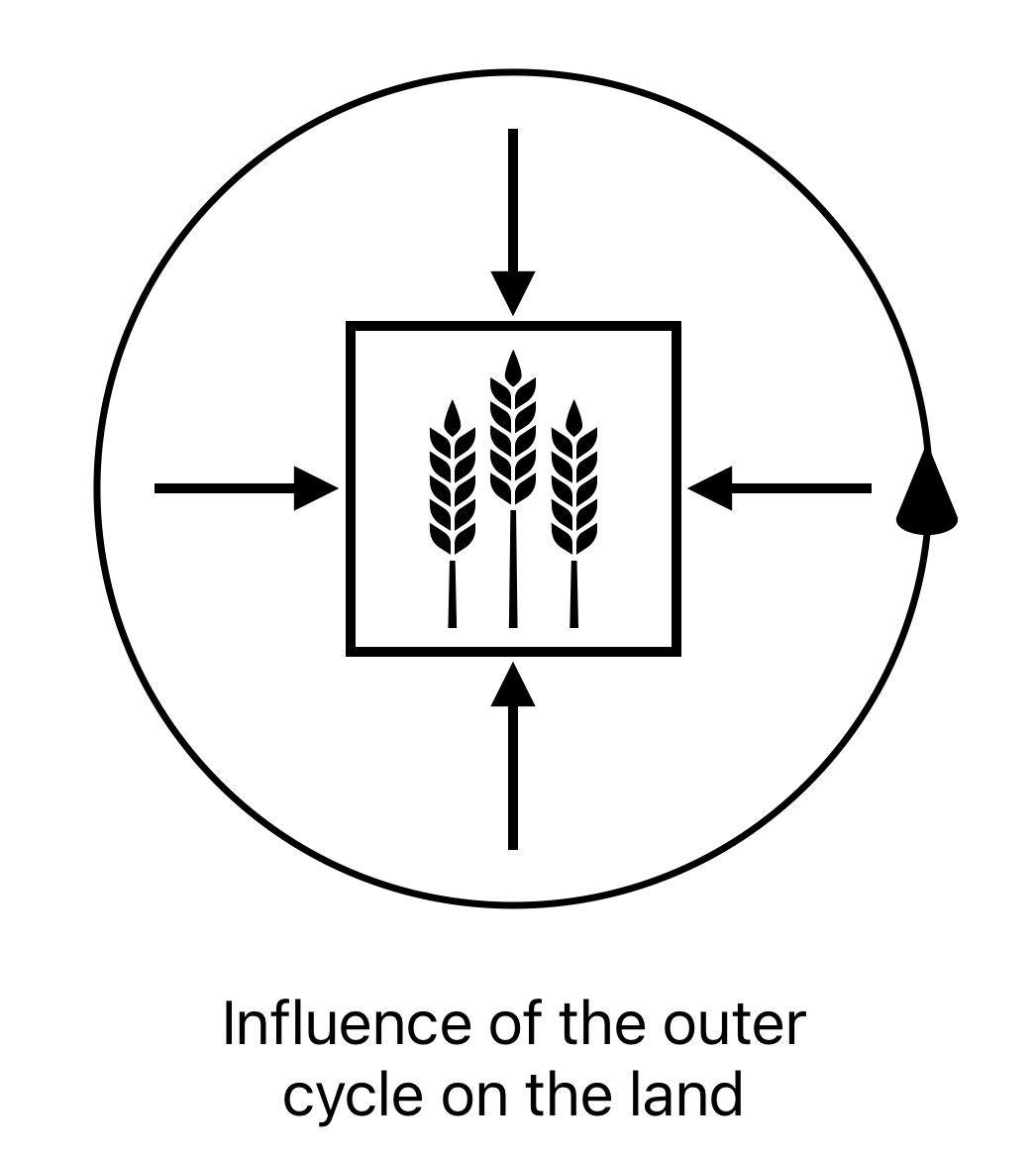

Cain is the farmer, the representative of cultivation. As the older brother, Cain is the inheritor of the land and it is fitting that he works on it. He is blessed with the inheritance, but cursed because of the earth. Cultivation is the process of working the land in accordance with the seasons (the heavenly and outer cycle of time) to produce fruits from the earth. It is heavily dependent on the transformative power of time, as well as openness to the environment (sun, air, rain, animals, etc). Therefore we can associate cultivation with labor and the influence of the “outer cycle.”

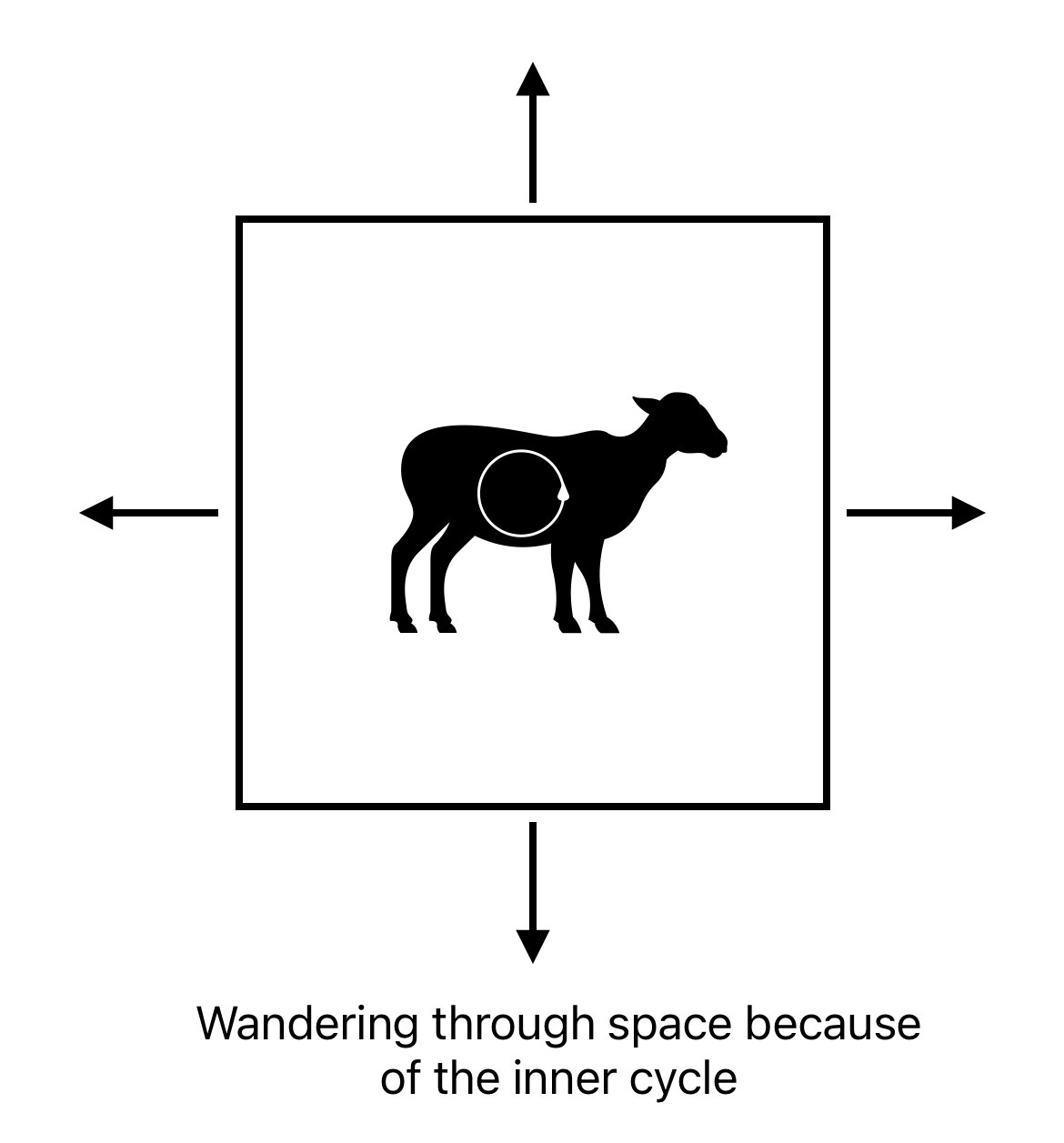

Abel on the other hand, is the nomad and the representative of shepherding and rumination. As the younger brother, Abel has no inheritance in the land and is not bound to it. Therefore he is free to let the animals do the work of making food for him. The process of rumination is that by which ruminant animals digest grass, turning it into flesh and milk. Unlike cultivation, the rumination cycle is internal to the animal and is therefore hidden from outside influence. It should be clear to the reader that there is a trade-off here, and there is a good reason why Abel’s name can be translated as “vanity.” He has little connection to the land and cannot build because he is constantly moving through space.

Once again, Guenon is helpful in describing the difference:

It could be said in a general way that the works of sedentary peoples are works of time: these peoples are fixed in space within a strictly limited domain, and develop their activities in a temporal continuity that appears to them to be indefinite. On the other hand, nomadic and pastoral peoples build nothing durable, and do not work for a future that escapes them; but they have space before them, not facing them with any limitation, but on the contrary always offering them new possibilities.

The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, p. 147

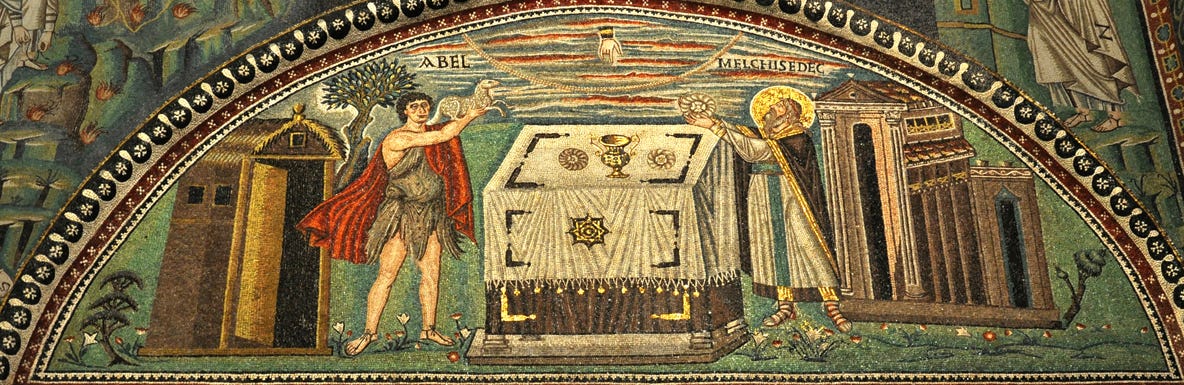

“In the process of time,”1 the two brothers bring offerings before God. Traditional depictions of this event show Abel lifting up a first-born lamb to God, while Cain is lifting up a bushel of wheat (the fruits of the ground). The depictions often show a fire from heaven coming down to consume the lamb, leaving Cain’s sacrifice untouched.

This event is a further development in the problem of the cursed earth and communion with God. It is man’s role to unite the earth to God, therefore it is a problem that Abel’s sacrifice is not bound to the earth in the same way that Cain’s is. Cain’s frustration is valid. As the inheritor of the land, it is his role to offer a pleasing sacrifice to God. In response the Lord says, “If you do well, will you not be accepted?”2 Cain is given an opportunity for redemption. He is given more time, and perhaps an opportunity for cooperation with his brother.

The text does not give a definite answer as to why Cain murders Abel. We may speculate that it was due to jealousy or pride. Either way, it seems that Cain’s goal was to fill his brother’s role. He desired to stand in the gap between God and earth, both working the earth and making offerings to God. But he did not “do well.”

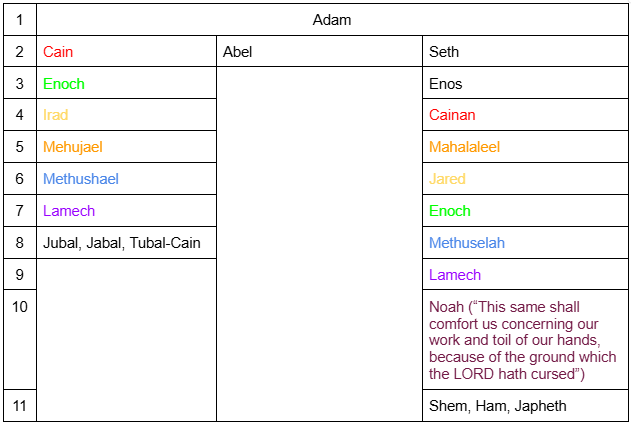

The result is that Cain, like his father, is cursed from the ground once more. “And now art thou cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother’s blood from thy hand; when thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength; a fugitive and a vagabond shalt thou be in the earth.”3 In attempting to mediate between heaven and earth in an improper fashion, Cain lost his inheritance. He now has neither the place of the shepherd nor that of the farmer. As time goes on, his lineage ends up expressing the combination he was seeking: Jabal (the nomadic cattle herder), Jubal (the musician), and Tubal-Cain (the metalworker). However, Jabal and Jubal only express the “vanity” of Abel, and all three are washed away in the flood.

Cain’s failed attempt at mediating between cultivation and rumination is juxtaposed with the lineage of Seth, who becomes the new inheritor of the land and also fills the role of Abel, as Eve says, “For God, hath appointed me another seed instead of Abel, whom Cain slew.”4 Where Cain failed, Seth steps in to mediate properly between heaven and the cursed earth. It is Seth’s line which survives the flood through Noah, the 10th generation beginning with Adam. Therefore Noah (meaning “rest” or “comfort”) represents a union of the two brothers, Cain and Abel. For this reason when he is born, his father names him saying, “This same shall comfort us concerning our work and toil of our hands, because of the ground which the LORD hath cursed.”5 He is a new Adam who has a renewed relationship with the earth.

When Noah went out of the ark, he first made an animal sacrifice to God according to the pattern of Abel. In response, God says “I will not again curse the ground any more for man’s sake.”6 At this moment Eve’s prophecy regarding Noah’s relation to the ground is fulfilled. After the lifting of the curse from the ground, Noah becomes a husbandman or more precisely “a man of the soil.”

Noah, as the husbandman, incorporates the inner cycle of rumination into cultivation through the technique of fermentation. Both wine and leavened bread are products of fermentation. For fermentation to occur, the outside cycle of time must mature the fruit. Then the fruit must be further exposed to the outside influence of the air in order to begin fermenting. When the fermentation process has begun, there needs to be an artificial period of rumination. The fermented fruit or grain must be covered to prevent further outside influence. This is the hidden or inner cycle.

Noah participates in meta-fermentation when, “he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.”8 If we understand the wine to be similar to the ferment that comes from outside influence, it has initiated the process of fermentation in Noah, and he must remain hidden for the process to be complete. However, the artificial rumination is cut short by Ham. Once again the sacrifice of Cain fails. Keeping the inner cycle hidden is proven to be difficult. This becomes a recurring pattern in the story: the cycle of transformation is cut short by impatience and pride.

The fulfillment of the process of fermentation, initiated by Noah, is found in leavened bread and wine. We can now see that the symbol of bread and wine as a sacrifice is not arbitrary and is connected to the first story following exile from the garden. It is the fulfillment of the role of Cain, and the offering proper to the inheritor of the “cursed earth.” Cain’s offering of a bushel of wheat can be juxtaposed with that of the mysterious priest Melchizedek: “And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God.”9 Perhaps if Cain had learned the inner cycle from his brother, he could have “done well” by bringing bread before God. In this way, Melchizedek is the redeemed Cain, the priest-king. Both the psalmist and the author of the letter to the Hebrews agree in identifying Melchizedek, the priest-king who brings forth bread and wine, as a type of Jesus.

My intention in drawing out this pattern from the story of Cain and Abel is not to claim that it is the only pattern in the story. Certainly the stories in Genesis and early on in the Bible can be understood as “seed stories.” They contain many far reaching implications, some of which may seem to contradict each other. One of the implications which I cannot address here is the line of thinking concerning animal sacrifice. It is clear from the new testament writings that the death of Jesus fulfilled the pattern of animal sacrifice. Saint John writes that Jesus is “the lamb slain from the foundation of the world.”11 I am certain that the connection between the sacrifice of Abel and that of Christ has been explored by others and bears much fruit.

Of course, the mystery of the eucharist goes far beyond what has been outlined here (and perhaps what can be expressed in words). Jesus’ equation of the bread and wine (products of fermentation) with his body and blood (products of rumination) is the complete solution to the duality set forth in the brothers Cain and Abel. I cut myself short here in awe, not daring to say more than is appropriate about such a luminous mystery. I do dare, however, to highlight the significance of raising up bread and wine, the fruits of the earth transformed into a holy offering by the powers of time. It would be a mistake to diminish the mystery of the bread and the wine, speaking only of the body and the blood. To do so would be to lose sight of Jesus as the King, who raises up the cursed earth into an honorable sacrifice.

Genesis 4:3

Genesis 4:7

Genesis 4:11

Genesis 4:25

Genesis 5:29

Genesis 8:21

Rene Guenon: “In this way is revealed the correspondence of the cosmic principles to which, in another order, the symbolism of Cain and Abel is related: the principle of compression, represented by time, and the principle of expansion, represented by space.”

Genesis 9:21

Genesis 14:18

Mosaic in the Basilica San Vitale, 6th century

Revelation 5:6

awesome exploration on exquisite Biblical symbolism

as you point out, cultivation possible on both ends in reconciling the soil and the herd. I don't see as clearly the nature of Cain's realm as subject to an outer influence, since Abel's vocation also subject to the same fermentative principle. Plants derived from a composition of soil are like animals derived from a reliance on the same composition of elements ((sun, air, rain, animals for plants and sun, air, rain, pasture, for animals). In that sense, both carry the mystery of fermentation , though indeed Cain's side engenders more of a death principle ("more" work, time interval, etc.), though Abel would have to face down predators..

in my reading of the patterns, the idolatry of Cain is of born of pride, fostered within himself, by way of a prideful heart (offended at the choice of blessing at the sacrifice), the technology of this pride was violence-force. Force pursues dominion in lieu of cultivation as dominion, one is born of pride, the other of communion. Great exploration of Noah's redemptive lineage, and his consummation of the fermentative principle (the ark was creative construction of natural elements, which is a fermentative process)

Also whats so lovely to me is that death is at the heart of both of these means, force and husbandry, as the curse stipulates, only one is suffered unto pride and the other by love.

I never thought about the fact that (at least from my reading) there was nothing specifying that the sacrifices had to be brought at the same time. That not only could Cain could have waited after the rejection; but the very fact that he brought an improper sacrifice in the first place implies that he may have only brought it due to cain bringing his.